Orange Crush sits alongside Industrial Artifacts blog alumni HERE, HERE, and HERE as another Keurig Dr Pepper brand with great sought-after antique advertising. However, of the historical products still in production today, Orange Crush comes with a pretty confusing beginning. At the turn of the last century, the pre-prohibition soda wars had many people stepping on each other’s toes. This means the official stories are sometimes a lot simpler than what can easily fit into a blog, and blogs tend to perpetuate problems by copying off each other - something we strive to avoid in favor of accuracy. We’ll go over what we know in attempt to clear up some of the confusion, but the man at the center of this Orange Crush blog post is Clayton James Howel, a boisterous Chicago businessman who was scammed out of his own name, yet turned it around to produce the most popular orange soda in history.

THAT'S HOWEL WITH ONE "L"

Clayton James Howel was born on April 13, 1878 in Centre, Alabama, a small town on Weiss Lake in Cherokee County. His parents, James Howel and Mary E. Sparks, moved the family to Fort Worth near the turn of the last century. Clayton would be in his 20s, looking for work in Fort Worth which was originally an army outpost established in 1849. By the time the Howels arrived, Fort Worth was one of the largest cattle markets in the world giving it the nickname "Cowtown."

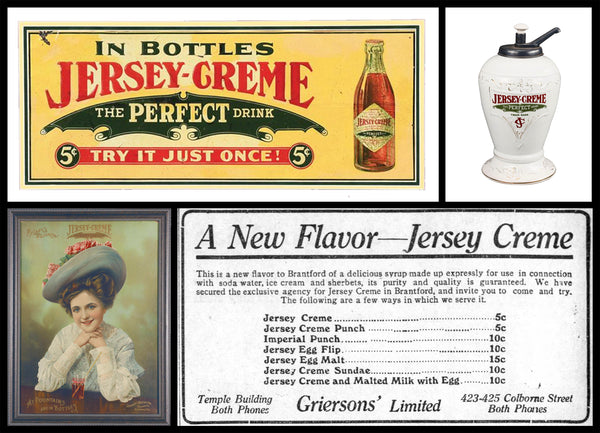

Clayton wasn't interested in cows. He was interested in beverages. So he went to work for Jersey Creme Company. Cream Soda, which has its own contentious history, was also on the rise (you can find the bizarre original recipe HERE, middle of the page) and Jersey Creme Co was a fresh face established in Fort Worth in 1905 with a laboratory where new soft drink flavors were created. Once a syrup was perfected, it was manufactured in Jersey Creme’s factory in Chicago, and sent around the country. Howel transferred to Chicago with Jersey Creme where he ran into an Orange Crush beverage that was created by J.M. Thompson in Chicago around 1906. Thompson's drink was not meant to be carbonated, simply an orange beverage, but the taste was so fantastic, Howel would buy the rights to it, tasking his company’s laboratory in Texas to create a fizzy version of the orange beverage. However, like many companies out of Fort Worth, Jersey Creme had a legitimate side, and a scammy side. This is where things get a little complicated.

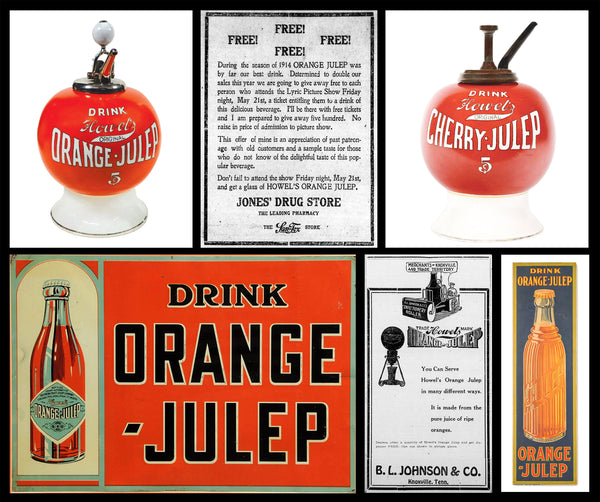

[INSERT NAME]'S ORANGE JULEP

According to the 1913 court case Luckett vs Orange Julep Co. (eventually settled in 1917), a drink called Orangeade by D. H. McDonald was outselling Jersey Creme, even though Orangeade was not shelf stable and had to be consumed immediately after it’s production. Clayton Howel assigned Claude Johnstone, a syrup manager of Jersey Creme, to create an orange carbonated drink that tasted as fresh as Thompson's Orange Crush and McDonald's Orangeade, but was carbonated and could sit on the shelf for later use. Claude Johnstone was not a chemist. His only schooling was from International Correspondence School, a “school-through-the-mail” program. Still, Johnstone produced an suitable orange drink in 1911, and by early 1912, production launched for "Howel’s Orange Julep."

Alfred M. Luckett, vice-president and manager of Jersey Creme, spent upwards of $20,000 a year (roughly $650,000 today) in advertising for Howel’s Orange Julep. Three Jersey Creme men - T. E. Blanchard, W. G. Newby, and W. C. Stripling - formed Southern Fruit Julep as a subsidiary of Jersey Creme to manage the new beverage and future fruit variations. Clayton James Howel even trademarked his own name to keep the branded product "Howel's Orange Julep" from being duplicated. What no one trademarked were the words “Orange Julep” nor did they patent the recipe. The reason why no one patented the recipe is because - according to Johnstone in the lawsuit - the recipe changes from time to time, sometimes because of the whim of executives, sometimes because of availability of raw materials to create the syrup. There are many ways to get to the same flavor, especially when financial profits are on the line. Johnstone described himself as not being the originator of the orange drink (because that would be J. M. Thompson), while also claiming to be the sole person responsible for its creation. So in 1913, Claude Johnstone left Jersey Creme, opened up his own company in St. Louis called “Orange Julep Company,” and started to distribute “Johnstone’s Orange Julep," trademarked "The Original.”

The lawsuit settled with Johnstone because recipes change regularly, and all this fuss was just a matter of branding. But on appeal in 1917, the court settled that the formula (varied or not) belonged to Jersey Creme, Howel was mislead by Johnstone, and all the parties involved would refrain from “making or marketing Orange Julep of any kind or under any formula…” until Johnstone settled his debt with Jersey Creme. This obviously took some time. The newspaper ad in the above pic comes from the Mississippi Times, April 12, 1918, page 4 - more than a year after the May 1917 settlement.

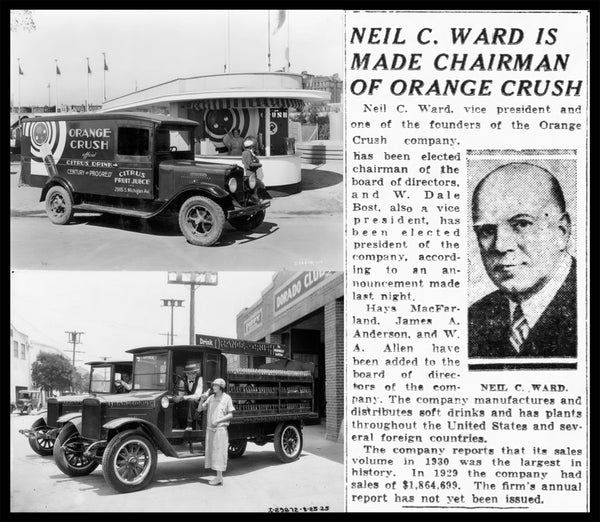

WARD TO THE RESCUE

A year or so before the May 1917 settlement, Howel had moved on from Jersey Creme and was working with a chemist named Neil Ward, who became a pivotal part of the Orange Crush story. There are many misconceptions about Mr. Ward in other blogs, so, we are going to clear up a few things. Neil Callen Ward was born November 12, 1882 in St. Joseph, Michigan to Henry Charles Ward and Mary Ann Wilson. In the late 1890s, the family moved to Greenfield, Tennessee. He went to Harvard in 1905 to pursue a degree in Chemistry, but lasted only 2 weeks before he accepted a job offer with Cooper Wells, & Co, a company that manufactured hosiery in his hometown of St. Joseph, Michigan. In 1910, Ward moved to California to be the superintendent of the Los Angeles Ice and Cold Storage Company where he became familiar with the manufacturing of flavor extracts, re-igniting Ward's love of chemistry. This is where he crosses paths with Howel’s Orange Julep.

In 1911 Neil and Clayton are working together on an orange drink called Orange Crush - using Thompson's original name, but opting to "crush" the oils out of the orange peel instead of orange juice for the flavor. We call it “zest” today, but in the 1910s, it was a great way to boost the orange taste without depending on the fluctuating quality of orange juice. One thing we can assume is Howel harked back to D. H. McDonald’s popular Orangade and its freshness by separately adding pulp to their Orange Crush drink - a feature that lasted until the 1930s, even though the beverage had no orange juice in it until the 1920s.

THE ORANGE CRUSH LEGACY

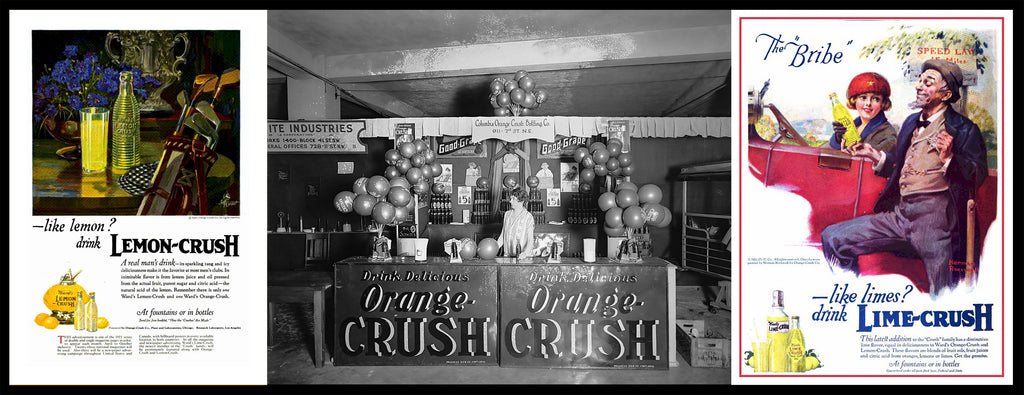

In 1916 with the Orange Julep lawsuit not fully settled, Clayton Howel avoided any named association with any orange drinks, letting Neil take the reins as the duo introduced "Ward’s Orange Crush." Lemon Crush came out in the 1920s, followed by other flavors like grape, lime, and strawberry. Orange Crush quickly expanded to international markets, and is currently found in 30 countries.

Ward took over as president in 1931 until he passed away in 1939. A local Chicago conglomerate Consolidated Foods Corp. bought Hires Root Beer from the Hires family in 1960, only to sell Hires to the Orange Crush Company in 1962. Clayton James Howel passed away in 1964. Proctor and Gamble purchased Crush in 1980, and in 1989 Cadbury Schweppes acquired Crush, which brings us Keurig Dr Pepper, as mentioned in the intro paragraph.

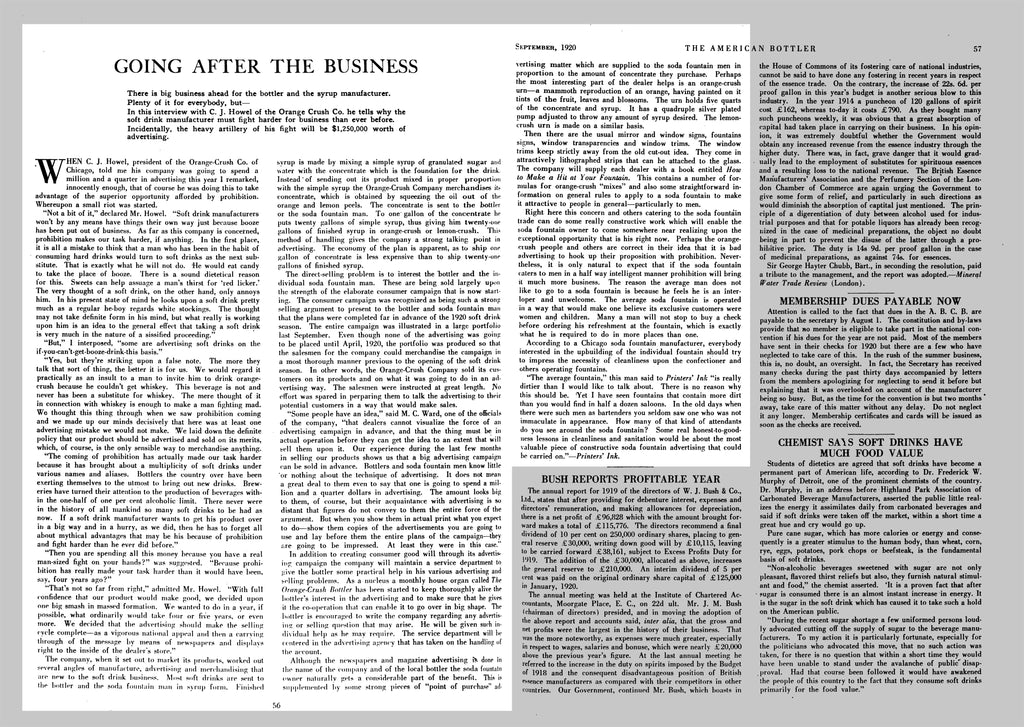

Point of interest: carbonated drinks were important to the Christian Temperance movement looking to ban alcohol everywhere they could. The common belief among them was the fizz and suds of the carbonation drink would help satisfy those who craved the ‘burn’ of hard liquor. No one seemed to have a problem with wine and beer, just the "hard stuff." If you're thinking that a bubbling, effervescent soda beverage isn't a great substitute for whiskey, you're not alone. At the end of this blog, there’s an interview of Clayton Howel from the September 1920 American Bottler trade magazine. From the first few paragraphs, you get a great glimpse of the rambunctious businessman, and as it turns out, he was very much correct about the fallacy that people who enjoyed hard “licker” would find cold gaseous fruit drinks a proper substitute. It’s quite an interview and, fair warning, the language is very much of the time.

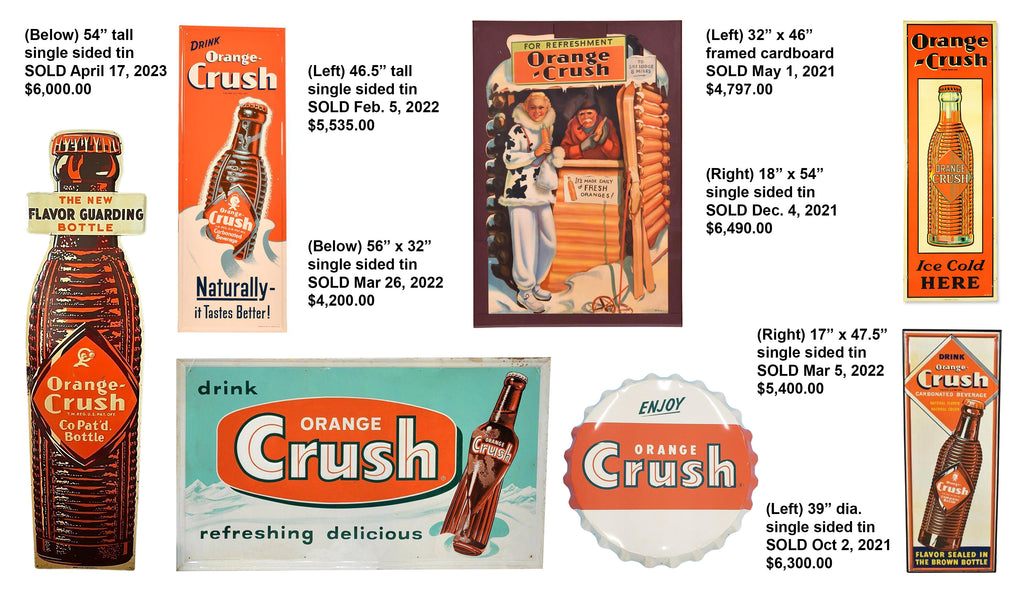

HOW MUCH ARE ORANGE CRUSH SIGNS WORTH?

There are a few brands covered in this post, so we’re going to touch on them. There's going to be a lot of soda ceramic soda dispensers which we've not covered before. According to the article at the end of this blog, they are actually called "urns," and were an integral part of advertising. Instead of sending out finished syrups to bottling plants and soda fountains, Howel sent a concentrate, and the bottling plant or soda jerk would need to mix 1 part concentrate with 20 parts simple syrup (or sugar water), producing 21 parts of finished Orange syrup that would be held in these dispensers. From there, a soda jerk would dispense the finished syrup as needed, mixing with carbonated water, phosphate soda, etc. As you can imagine, shipping a gallon of concentrate is much cheaper than shipping 20 gallons of finished syrup.

Jersey Creme Company (first picture of this blog) lasted in some form until the 1930s, but most of what's out there in signs are mostly 27 1/2” x 13 3/4” tin (sometimes called "tin-tacker" signs), and are currently in the $500-700 range. The extremely rare Jersey Creme ceramic syrup dispenser with pump goes from $2,500-$3,500. These dispensers were used in pharmacies and drug stores with soda counters where the soda jerk would create the carbonated drink or ice cream sodas.

In considering how Jersey Creme spent our equivalent of $650,000 in today's money on advertising for Howel’s Orange Julep, we get the idea that most of this was spent on the bright orange syrup dispensers (second pic of this blog). When you think about it, walking into a drugstore soda fountain, you’d be faced with lots of advertising signs, but seeing a large orange on the counter where you order a drink is pretty powerful marketing. In the 2024 market, dispensers in perfect condition with pump are consistently bringing in over $2,000 each. Signs are reasonably priced at around the $500-range, and of course it's dependent on condition and size. If you see one that has "Orange-Julep" hyphenated, it's probably Howel's as Orange-Crush used to be hyphenated as well.

Johnstone’s Orange Julep (third pic of this blog) has signs, trays, and even dispensers, but not much over $600. The last purchase of a Johnstone’s Orange Julep tilting dispenser was sold for only $436.97 on April 1, 2023. It’s remarkably smaller than the other dispensers. Considering the story of Johnstone, this seems overly generous.

Complete Orange Crush dispensers are also consistently over $2,000, but the Lemon and Lime Crush dispensers can get up to $8,000. The Orange Crush signs are varied, but there is a consistency, which really speaks well to the power of the brand. Below is a small example of the Orange Crush signs that have sold and their prices, including those with and without the Orange Crush mascot, Crushy. It’s just a small example of signs out there, and a testament to the power of advertising.

If you're a vintage bottle collector, PRINT Magazine has you covered with an excellent rundown of the "crinkly" bottles HERE.

CLAYTON JAMES HOWL'S 1920 INTERVIEW WITH AMERICAN BOTTLER

Click on the image below to embiggen.

Leave a comment