The meticulous craft of mapmaking has always existed at the crossroads of art, math, and science. But for the majority of human existence, maps weren't readily accessible nor consistent, and those that were presented inaccuracies based on the map maker's bias and time limitations in creating them. Two men changed that in a profound way, making maps easily accessible, easy to interpret, and with constant updating accuracy.

William Henry Rand

We start this story with a man named William Henry Rand (on the left), born May 2, 1828 in Quincy, Massachusetts. William was 12th child and 7th son of his parents… his father, John Rand, a local Boston-area minister. William spent his youth split between school and working in the printing offices of his brothers, Franklin and George, who later founded Rand, Avery, and Company with steam-driven printing in Boston.

More than a year after James W. Marshall struck gold at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California, William Henry couldn't help but join the “California Gold Rush,” taking the long way to the West Coast via Cape Horn. His time in the mines were not as successful as his co-founding of the state's first newspaper, the Los Angeles Star. So he returned to Boston and married Harriet Robertson in 1855 and a year later he moved his new family to Chicago, Illinois. By June of 1856, William opened a printing business that eventually included printing the Chicago Tribune.

We can sell your antique maps and advertising

Andrew McNally

2 years later - in 1858 - Andrew McNally walked into Rand’s printing shop and asked for work. Andrew was born in Armagh, Ireland, and had come to the United States through New York City in 1857. McNally was also a printer by trade, and with his expertise he quickly went from printer, to foreman, to partner. By 1859, Rand and McNally were running all of the Chicago Tribune's printing. After the Civil War was over, William Henry sold his interest in the Chicago Tribune and focused on his growing business. Rand, McNally and Company was officially incorporated in 1868.

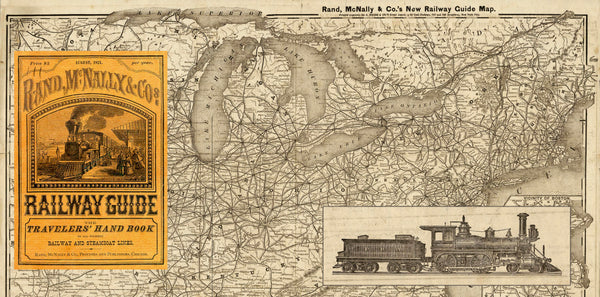

Rand McNally & Co started by publishing business directories and railroad guides, but the game changer came in 1872 when the company created their first map - a railroad guide printed with wax engraving which was low in cost to produce and simplified the process of making corrections, thus producing a product that was continuously up-to-date.

Check out these four 1920s cartographer's maps

Indexed Pocket Maps

It was a hit that escorted the company into being the largest manufacture of maps in the United States by 1880, employing over 250 men and women with annual sales exceeding $500,000.00. This growth continued as the company expanded to atlases and textbook publishing… and indexed pocket maps such as this one from 1878.

Need storage for your map collection? We've got you covered

The Glass-Front Cabinet

That brings us to this 14” wide x 22” tall Rand McNally and Company Indexed Pocket Maps display case (below), used from the 1880s. It is absolutely remarkable condition considering it is about 130 years old. It is about 9" deep, a perfect fit to the pocket maps shown above. Rand McNally is famously noted as helping create the United States highway numbering system. That took place some 40 years after this cabinet was built.

Rand McNally Chicago Folklore

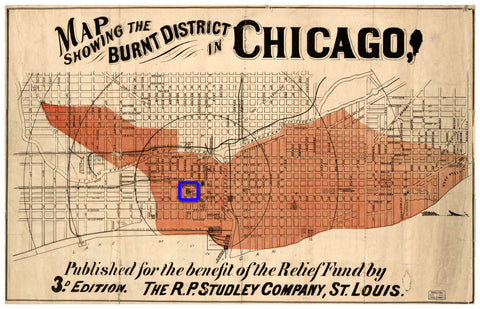

The Great Chicago Fire took place between October 8th through 10th, 1871, destroying about 3.3 square miles of the city, killing over 300 people and leaving over 100,000 residents homeless. Being on Madison Street between Clark and Dearborn (marked in blue in the pic below), Rand McNally and Company was in the middle of the devastation.

Local PBS affiliate WTTW and Chicago History Museum remembers the Great Fire

According to company folklore, the business Willam Rand and Andrew McNally had workers take two of the company’s printing machines and bury them in the sandy beach of Lake Michigan. After the fire had ended, the printers were retrieved and Rand McNally & Co. was up and running in a rented space, and continued to print while the city rebuilt. They were able rebuild their space at 77 and 79 Madison Street, continue their printing jobs, and work on the 1872 Railroad guide all at the same time.

Leave a comment